To the life-size crucifix

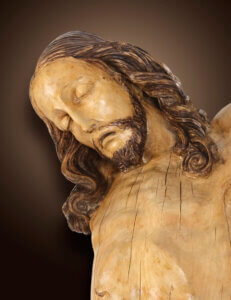

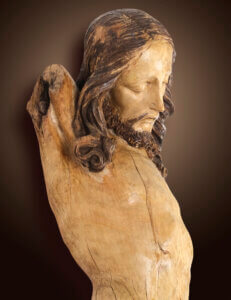

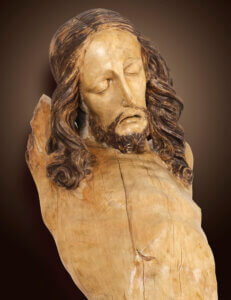

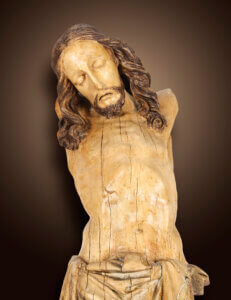

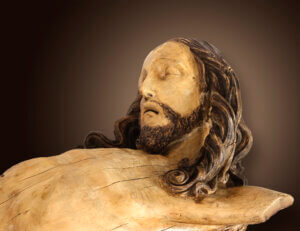

In his “sack”-like hanging corpus, whose arms are originally to be presented in an obliquely rising pose by virtue of the left shoulder attachment and whose feet are also missing, the subtle formal interpretation of the incarnation contained in its sculptural surfaces and the corrugated articulation of the strands of hair, which are given laterally in large-formed waves, as it were, dripping down, and – above all – in the physiognomic expression, in which the pain previously overcome in terms of content has apparently come to a congealing calm. In striking contrast to the emphatically vertical posture of the corpus, whose axiality is given a tense nuance by the gentle inclination of the upper body to the left and in chord with the parallel legs, the head tilted to the left in its intense facial expression in the strikingly forward-leaning pose results in an emphatically vital and at the same time expressive component in the sculptural realization despite the “being dead” content. It is precisely this articulated inclination of the head, in conjunction with the anatomically exact reproduction of the ribcage and the musculature of the parallel knees, that lends this sculpture the expressive coefficient of tension that gives this crucifix its obvious “special status” in comparison to numerous thematically similar carved works. Between the “anatomically” precisely rendered parts of the ribcage and legs, the loincloth with its pointed parabolic, downward-pressing bowl folds and the drapery ends hanging down the flanks of the hips create a restless contrast that corresponds effectively to the lively “condensation of forms” in the hair of the head. Incidentally, both the latter and the former are the only zones within this sculpture where remnants of the polychroming to be assumed can be found in different dimensions. Just as the “undulating” surface on the ribcage clearly differentiates the area of the heart and lung sections in contrast to the sinking pit of the stomach – and the strikingly linear contour of the lance just at the right cartilage arch in its quality of sudden success is given as an effective contrast to the “nobly smoothed” incarnate – so this creative methodology culminates in the physiognomy, where the high “calotte”-like curved forehead in chord with the widely curved eyebrows in their continuous transition to the long nose in coordination with the deep-set eye sockets with their almost completely closed, stereometrically rounded lids, as well as in the “spherically curved” cheeks in the upwardly curved “crescent moon”-like mouth separated by the beard, expresses in a restrained subsuming the pain of death previously suffered “having come to rest”.

Although numerous cracks of varying lengths and widths can be seen throughout the corpus within this monolithic block of wood, suggesting that the figure was mostly present in the open space at times, the fact that there are no such cracks on the head is explained by the strong inclination of the head itself, which formed an “umbrella”-like protection, as it were! As much as the repeatedly mentioned inclination of the head of Christ in this extraordinarily striking form and in addition to the tension-intensive contrast to the “sack-like” hanging body may initially seem strange, this very fact serves as an essential criterion for an art-historical classification: in the so-called Styrian “Mühlau Crucifixus” (today in Graz, Alte Galerie of the Joanneum, Schloss Eggenberg) from the 3rd quarter of the 13th century, which is known as the “Mühlauer Kruzifixus” (today in Graz, Alte Galerie of the Joanneum, Schloss Eggenberg). In the so-called Styrian “Mühlau Crucifix” (today in the Alte Galerie of the Joanneum, Eggenberg Castle, Graz) from the third quarter of the 13th century, which soon gave rise to successor works, a genuinely Styrian origin is also unmistakable for the crucifix in question, which represents an unmistakable late Gothic variant of this type from the last decade of the 15th century. In view of the outstanding sculptural quality of the carving, we can assume a prominent milieu, both on the part of the presumed commissioner and even more so on the part of the executing carver. The extent to which the original purpose of this crucifix could be relevant for the Church of the Holy Spirit in Bruck an der Mur (completed in 1493), which was co-donated by the Bruck merchant Kornmesser, can at best be assumed to be “speculative”, at least for the time being.

Dr. Arthur Saliger